How To Transform Into An Animal In Real Life

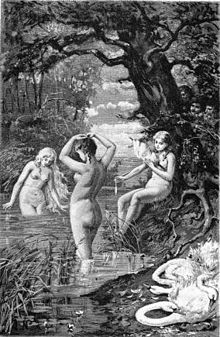

Valkyries, having shed their swan skins, appear equally swan maidens.

Therianthropy is the mythological ability of human beings to metamorphose into other animals by means of shapeshifting. It is possible that cave drawings found at Les Trois Frères, in France, depict ancient beliefs in the concept.[ citation needed ]

The best-known form of therianthropy, called lycanthropy, is found in stories of werewolves.

Etymology [edit]

The term "therianthropy" comes from the Greek theríon [θηρίον], meaning "wild animal" or "beast" (implicitly mammalian), and anthrōpos [ἄνθρωπος], meaning "man". It was used to refer to creature transformation folklore of Europe as early on equally 1901.[i] Sometimes the term "zoanthropy" is used instead.[2]

Therianthropy was used to draw spiritual beliefs in animal transformation in a 1915 Japanese publication, A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the End of the Meiji Era.[iii] I source, The Human Predator, raises the possibility the term may have been used equally early as the 16th century in criminal trials of suspected werewolves.[four]

History of therianthropy and theriocephaly [edit]

Therianthropy refers to the fantastical, or mythological, ability of some humans to change into animals.[5] Therianthropes are said to modify forms via shapeshifting. Therianthropy has long existed in mythology, and seems to be depicted in ancient cave drawings[6] such as The Sorcerer, a pictograph executed at the Palaeolithic cave drawings constitute in the Pyrénées at the Les Trois Frères, French republic, archeological site.

'Theriocephaly' (Gr. "animal headedness") refers to beings which have an animal head attached to an anthropomorphic, or human, body; for instance, the fauna-headed forms of gods depicted in ancient Egyptian religion (such as Ra, Sobek, Anubis).

Mythology of man shapeshifting [edit]

Shapeshifting in sociology, mythology and anthropology generally refers to the alteration of physical advent from that of a human being to that of some other species. Lycanthropy, the transformation of a human into a wolf (or werewolf), is probably the best known class of therianthropy, followed by cynanthropy (transformation into a dog) and ailuranthropy (transformation into a cat).[7] Werehyenas are nowadays in the stories of several African and Eurasian cultures. Aboriginal Turkic legends from Asia talk of course-changing shamans known as kurtadams, which translates to "wolfman".[ citation needed ] Aboriginal Greeks wrote of kynanthropy, from κύων kyōn [8] (or "canis familiaris"), which applied to mythological beings able to alternating between dog form and human form, or who possessed combined dog and human anatomical features.[ citation needed ]

The term existed by at least 1901, when it was practical to stories from Mainland china about humans turning into dogs, dogs becoming people, and sexual relations between humans and canines.[9] Anthropologist David Gordon White called Central Asia the "vortex of cynanthropy" because races of canis familiaris-men were habitually placed there by ancient writers. The weredog or cynanthrope is besides known in Timor. Information technology is described as a human-canine shapeshifter who is capable of transforming other people into animals, even against their volition.[ commendation needed ]

European folklore features werecats, who can transform into panthers or domestic cats of an enlarged size.[10] African legends describe people who turn into lions or leopards, while Asian werecats are typically depicted as condign tigers.[ citation needed ]

Skin-walkers and naguals [edit]

Some Native American and First Nation legends talk almost pare-walkers—people with the supernatural ability to turn into any animal they desire. To exercise so, however, they first must be wearing a pelt of the specific brute. In the folk religion of Mesoamerica, a nagual (or nahual) is a human being who has the power to magically turn themselves into animal forms—about ordinarily donkeys, turkeys, and dogs—simply can also transform into more powerful jaguars and pumas.[ citation needed ]

Animal ancestors [edit]

Stories of humans descending from animals are found in the oral traditions for many tribal and clan origins. Sometimes the original animals had causeless human class in order to ensure their descendants retained their human shapes; other times the origin story is of a human marrying a normal animate being.

N American indigenous traditions mingle the ideas of bear ancestors and ursine shapeshifters, with bears often being able to shed their skins to assume human form, marrying human women in this guise. The offspring may be creatures with combined anatomy, they may exist very cute children with uncanny strength, or they may exist shapeshifters themselves.[11]

P'an Hu is represented in various Chinese legends every bit a supernatural dog, a domestic dog-headed man, or a canine shapeshifter that married an emperor'south girl and founded at least 1 race. When he is depicted as a shapeshifter, all of him tin get human being except for his caput. The race(s) descended from P'an Hu were often characterized past Chinese writers as monsters who combined human and dog anatomy.[12]

In Turkic mythology, the wolf is a revered animal. The Turkic legends say the people were descendants of wolves. The fable of Asena is an one-time Turkic myth that tells of how the Turkic people were created. In the legend, a small Turkic village in northern China is raided past Chinese soldiers, with one baby left behind. An old she-wolf with a heaven-blueish mane named Asena finds the babe and nurses him. She afterwards gives birth to half-wolf, half-man cubs who are the ancestors of the Turkic people.[13] [14]

Shamanism [edit]

Ethnologist Ivar Lissner theorised that cavern paintings of beings with man and non-human fauna features were not concrete representations of mythical shapeshifters, simply were instead attempts to depict shamans in the procedure of acquiring the mental and spiritual attributes of various beasts.[15] Religious historian Mircea Eliade has observed that beliefs regarding fauna identity and transformation into animals are widespread.[16]

Animal spirits [edit]

In Melanesian cultures at that place exists the belief in the tamaniu or atai, which describes the animal counterpart to a person.[17] Specifically amid the Solomon Islands in Melanesia, the term atai means "soul" in the Mota language and is closely related to the term ata, meaning a "reflected epitome" in Maori and "shadow" in Samoan. Terms relating to the "spirit" in these islands such as figona and vigona convey a being that has not been in human form[xviii] The animal counterpart depicted, may take the form of an eel, shark, lizard, or another animal. This animate being is considered to be corporeal, and can empathise human spoken communication. It shares the same soul every bit its master. This concept is plant in similar legends which have many characteristics typical of shapeshifter tales. Amid these characteristics is the theory that death or injury would touch on both the human and animate being grade at in one case.[17]

Psychiatric aspects [edit]

Amongst a sampled fix of psychiatric patients, the belief of being office brute, or clinical lycanthropy, is generally associated with severe psychosis, just non always with any specific psychiatric diagnosis or neurological findings.[xix] Others regard clinical lycanthropy as a delusion in the sense of the self-disorder found in affective and schizophrenic disorders, or as a symptom of other psychiatric disorders.[xx]

Modernistic therianthropy [edit]

Therians are individuals who believe or experience that they are not-human animals in a non-biological sense. While therians mainly aspect their experiences of therianthropy to either spirituality or psychology, the manner in which they consider their therian identity is not a defining characteristic of therianthropy; equally long as a person identifies their sense of cocky as being that of a non-human brute, they can be considered a therian.[21] [22] The animal which a therian identifies every bit is known by the community as a "theriotype", and this can refer to either the animal they identify equally or, more specifically, their own non-human animal identity. For example, a therian who believes in reincarnation may use the word "theriotype" to refer specifically to their past life or, more generally, to indicate that they are speaking most the creature species they place every bit. Therians often apply the term "species dysphoria" to describe their feelings of disconnect from their human bodies and their underlying desire to alive as their theriotype.[23] The concept of species dysphoria has frequently been compared to gender dysphoria, in that there is a similar sense of incongruence betwixt the person'southward physical torso and their internal sense of cocky. Some not-human identifying people oppose this comparison, stating that "they are separate ... identities". Others intentionally parallel the two, highlighting the similarities.[24] Species dysphoria, or species identity disorder, has been proposed as a mental disorder.[25] A now-defunct therian website suggested a criteria for a diagnosis, based on the diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Gerbasi et al. noted the "striking" similarities between species and gender dysphoria, leading them to tentatively suggest a medical diagnosis of species identity disorder.[25] Others have compared species dysphoria with body dysmorphic disorder, terming it "species dysmorphia" instead.[26] A participant in Proctor's paper stated that they would consider it a course of neurodiversity, rather than a medical diagnosis, "unless it had major and negative impact on someone's life".[27] The identity "transspecies" is used by some, furthering the similarities between identifying as a dissimilar species and a dissimilar gender.[28]

Prevalence [edit]

In an online community survey of 523 non-human identifying people, 75.one% said they experienced species dysphoria, and 8.two% were unsure.[29] In a survey of 408 furries, a quarter responded that they experienced species dysphoria (although furries and otherkin are 2 separate, but frequently intersecting, groups).[xxx]

Shifting [edit]

Many therians depict experiences of temporarily feeling more in touch on with their theriotype than they do at other times, and this phenomenon is known by the community as "shifting", with the experiences beingness known as "shifts". Shifts can vary indefinitely in the length of time for which they are experienced, and the intensity with which they are felt. They can also be triggered intentionally, or unintentionally, usually by stimuli relating to a person's theriotype. While shifting is oftentimes regarded as a positive experience, the disruption caused by unintentional triggers, and heightened feelings of species-dysphoria, can also lead to therians experiencing shifts as negative experiences too. Shifts are normally experienced in a land of consciousness, although dream shifts (in which a therian might really believe they have the body of their theriotype) are an exception to this. Some therians attribute their knowledge of their own therianthropic identities to their experiences of shifting. For instance, a wolf therian might begin to identify as a wolf after experiencing dreams in which their body takes the grade of a wolf.

The therian community is generally considered to be a subculture of the otherkin community, which consists of individuals who identify as or connect with any fictional or non-fictional being. However, unlike otherkin, therians practise not place as fictional beings, and the two movements are culturally and historically distinct.[23] [ folio needed ]

See also [edit]

- Banjhakri and Banjhakrini

- Cynanthropy

- Man–creature hybrid

- Kelpie

- Kitsune

- Nagual

- Otherkin

- Selkie

- Shapeshifting

- Peel-walker

- Supernumerary phantom limb

- Theriocephaly

- Werecat

- Werewolf

- Werewolf fiction

- Werehyena

- Werejaguar

- Wererat

- Zoomorphism

Notes and references [edit]

- ^ De Groot, J.J.M. (1901). The Religious System of China: Volume Four. Leiden: Brill. p. 171.

- ^ Guiley, R.East. (2005). The Encyclopedia of Vampires, Werewolves & Other Monsters. New York: Facts on File. p. 192. ISBN0-8160-4685-nine.

- ^ Brinkley, Frank; Dairoku Kikuchi (1915). A History of the Japanese People from the Earliest Times to the Stop of the Meiji Era. The Encyclopædia Britannica Co.

therianthropy.

- ^ Ramsland, Katherine (2005). The Human being Predator: A Historical Chronicle of Serial Murder and Forensic Investigation. Berkley Hardcover. ISBN0-425-20765-X.

- ^ Edward Podolsky (1953). Encyclopedia of Aberrations: A Psychiatric Handbook. Philosophical Library.

- ^ "Trois Freres". Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved 2006-12-06 .

- ^ Greene, R. (2000). The Magic of Shapeshifting. York Beach, ME: Weiser. p. 229. ISBNi-57863-171-viii.

- ^ kynanthropy; Woodhouse's English-Greek Dictionary; (1910)

- ^ De Groot, J.J.M. (1901). The Religious System of People's republic of china: Book IV. Leiden: Brill. p. 184.

- ^ Greene, Rosalyn (2000). The Magic of Shapeshifting. Weiser. p. 9.

- ^ Pijoan, T. (1992). White Wolf Woman & Other Native American Transformation Myths . Piddling Rock: Baronial House. p. 79. ISBN0-87483-200-four.

- ^ White, D.G. (1991). Myths of the Dog-Human being . Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. p. 150. ISBN0-226-89509-two.

- ^ Cultural Life – Literature Turkey Interactive CD-ROM; 2007-08-eleven.

- ^ T.C. Kultur Bakanligi; Nevruz Celebrations in Turkey and Fundamental Asia Archived 2007-04-04 at the Wayback Machine; Ministry building of Civilisation, Republic of Turkey; accessed 2007-08-xi

- ^ Steiger, B. (1999). The Werewolf Volume: The Encyclopedia of Shape-Shifting Beings. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink. ISBN1-57859-078-7.

- ^ Eliade, Mircea (1965). Rites and Symbols of Initiation: the mysteries of birth and rebirth. Harper & Row.

- ^ a b Hamel, F. (1969). Human Animals, Werewolves & Other Transformations. New Hyde Park, NY: University Books. p. 21. ISBN0-8216-0092-3.

- ^ Ivens, Walter (January 1934). "The Diversity of Culture in Melanesia". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Bang-up Britain and Ireland. 64: 45–56. doi:10.2307/2843946. JSTOR 2843946.

- ^ Keck PE, Pope HG, Hudson JI, McElroy SL, Kulick AR (February 1988). "Lycanthropy: alive and well in the twentieth century". Psychol Med. 18 (one): 113–20. doi:10.1017/S003329170000194X. PMID 3363031.

- ^ Garlipp, P; Godecke-Koch T; Dietrich DE; Haltenhof H. (January 2004). "Lycanthropy—psychopathological and psychodynamical aspects". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 109 (1): 19–22. doi:10.1046/j.1600-0447.2003.00243.ten. PMID 14674954. S2CID 41324350.

- ^ Laycock, Joseph P. (2012). "We Are Spirits of Another Sort". Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. fifteen (three): 65–ninety. doi:10.1525/nr.2012.15.3.65.

- ^ Cohen, D. (1996). Werewolves . New York: Penguin. p. 104. ISBN0-525-65207-8.

- ^ a b Lupa (2007). A Field Guide to Otherkin. Megalithic Books. ISBN978-1905713073.

- ^ Robertson, Venetia Laura Delano (2006). "The Police of the Jungle: Self and Community in the Online Therianthropy Movement". The Pomegranate. 14 (2). folio 274 of 256–280. doi:10.1558/pome.v14i2.256.

- ^ a b Gerbasi, Kathleen; Bernstein, Penny; Conway, Samuel; Scaletta, Laura; Privitera, Adam; Paolone, Nicholas; Higner, Justin (2008-08-01). "Furries from A to Z (Anthropomorphism to Zoomorphism)". Club and Animals. 16 (3): 197–222. doi:10.1163/156853008X323376.

- ^ Clegg, Helen; Collings, Roz; Roxburgh, Elizabeth C (2019). "Therianthropy: Wellbeing, Schizotypy, and Autism in Individuals Who Cocky-Identify as Not-Human being" (PDF). Order & Animals. 27 (4): 403–426. doi:10.1163/15685306-12341540. S2CID 149663734.

- ^ Proctor, Devin (2018-09-29). "Policing the Fluff: The Social Structure of Scientistic Selves in Otherkin Facebook Groups". Engaging Scientific discipline, Engineering science, and Society. 4: 485–514. doi:10.17351/ests2018.252. S2CID 55833371.

- ^ Grivell, Timothy; Clegg, Helen; Roxburgh, Elizabeth C (2014). "An Interpretative Phenomenological Assay of Identity in the Therian Community". Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Enquiry. 14 (ii): 113–135. doi:10.1080/15283488.2014.891999. S2CID 144047707 – via Routledge.

- ^ Who-is-page, 2021, The 2021 Nonhumanity & Body Modification/Ornament Survey Results Breakdown, https://invisibleotherkin.neocities.org/files/BodyModification-DecorationSurveyResults.pdf

- ^ Plante, Courtney, N; Reysen, Stephen; Roberts, Sharon East; Gerbasi, Kathleen C (2016). FurScience! A Summary of Five Years of Inquiry from the International Anthropomorphic Research Project (PDF). Waterloo, Ontario, Canada: FurScience. ISBN978-0-9976288-0-seven.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Therianthropy

Posted by: sherrellsiondonsen.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Transform Into An Animal In Real Life"

Post a Comment