What Is The Disability Being Portrayed In Grey Gardens?

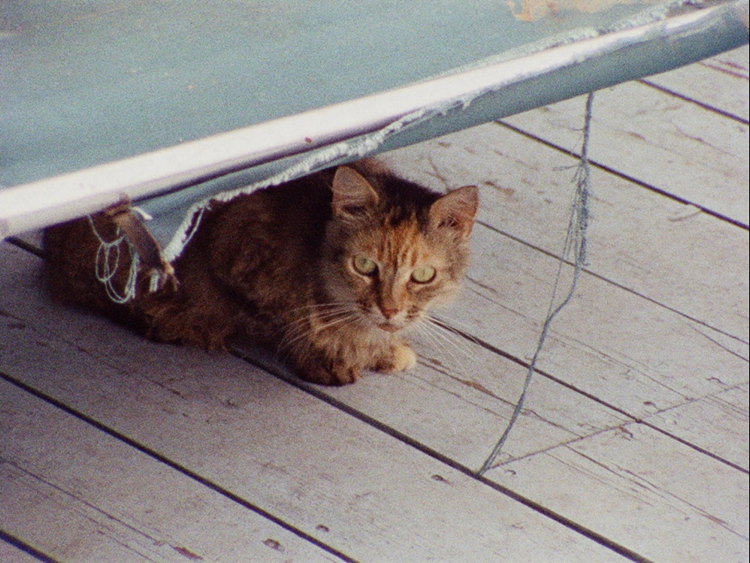

Truth is stranger than fiction. If the long-held cliché needs real-world proof, surely Edith Bouvier Beale and her daughter Edie are its embodiment. The eccentric duo, forever immortalised in Albert and David Maysles' enduring 1976 documentary Grey Gardens, lived together in a dilapidated mansion on Long Island surrounded by free-roaming cats (too many to count), raccoons (encouraged), mice and any other number of (un)invited wildlife. 'Big Edie' and 'Little Edie' respectively, aunt and cousin to Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, they lived in squalor amongst faded belongings that tell stories of youth, dreams and oft-recounted memories.

The Edies lived together for more than 20 years, spending most of their time squabbling, singing, shrieking, and talking across, over and above each other. Their unique mother-daughter bond was compounded by an insular environment and lack of contact with the outside world but was tinged with regret and bitterness. The unmarried Little Edie, who had dancer ambitions, was called back to the house to care for her mother and never left. She was on the verge of success; her chance was scuppered by duty. Understandably bitter, she dreamt of leaving, of returning to New York and glory. At the time of filming, she was 56-years-old (Edith is 82).

The Edies lived together for more than 20 years, spending most of their time squabbling, singing, shrieking, and talking across, over and above each other. Their unique mother-daughter bond was compounded by an insular environment and lack of contact with the outside world but was tinged with regret and bitterness. The unmarried Little Edie, who had dancer ambitions, was called back to the house to care for her mother and never left. She was on the verge of success; her chance was scuppered by duty. Understandably bitter, she dreamt of leaving, of returning to New York and glory. At the time of filming, she was 56-years-old (Edith is 82).

Together, the two sit on filthy sagging beds and look through yellowing scrapbooks that preserve their former glory. Here's Edith on her wedding day. There's Edie modelling swimwear at a charity fashion show. Over in the corner of the room is a painted portrait of Edith. A cat is defecating behind it. By capturing the true minutiae of both Edies, the Maysles' documentary preserves a way of life that's outside the realm of many but captures so much about society expectations, or fears of aging, and what it truly means to live as 'who' you are.

Part of its charm lies in the unexpected. This isn't a world 'normals' usually get a glimpse into and the documentary actually came about mostly by chance. Albert and David (who found fame with Gimme Shelter, a documentary chronicling a notorious Rolling Stones concert) were approached by Jackie Kennedy's sister, Lee Radziwell, who was interested in developing a filmed family album. As it turned out, there was little of interest to the Maysles' in the Bouvier family… apart from the two reclusive family members who lived in Long Island. Albert and David spent two months filming Edith and Edie, but when they showed Radziwell the footage, she demanded the negatives. Squalor-dwelling eccentrics? That wasn't the image that they wanted the world to see. But ironically, Edith and Edie enjoyed the experience so much (probably because it played into unrealised dreams) they invited the filmmakers back. Grey Gardens, the resultant feature documentary, become – and remains – a cult piece of cinema, and greatly contributed to the development and proliferation of cinéma-vérité. The naturalistic structure and lack of judgment (there's no voice-overs, introductions or attempts at historical context) place the emphasis firmly on Edith and Edie and the way they lived. The documentary raises more questions than it answers. What happened to the so-called Marble Faun (a handyman named Jerry who helped around the house)? How did the house become so squalid? Where does their money come from? What does Jackie think?

The Maysles' certainly captured some wonderful moments. Little Edie, who had a particularly idiosyncratic fashion sense and wore turbans (to hide alopecia) paired with upside-down skirt or retro bathing suits, practices her dancing in the empty hallway or reads horoscope predictions about a non-existent husband aloud. Constantly complaining about her weight, she steps on some bathroom scales, viewing the gauge through a pair of binoculars. Her tedious talk-pieces have no beginning or end; meandering rambles they speak volumes about her loneliness and isolation. Big Edie has a birthday party with very few guests, marking the occasion with a rare appearance downstairs. She berates Edie for not clearing the stairs properly. In spite of this humorous charm, it's hard not to wonder if the Edies were being exploited, if Grey Gardens is at best bad taste, at worst voyeuristic exploitation. So many quotes lend themselves to extensive psychological probing. When the cat defecates behind the portrait Big Edie remarks: "Well at least someone is doing what they want." Similarly, from Little Edie: "It's very difficult to keep the line between the past and the present… Do you know what I mean?".

Certainly – and perhaps tragically – the documentary presents Big and Little Edie at their least glamorous, with little sympathetic context of how they ended up there. Prior to filming, they were threatened with eviction because the local council considered the house too squalid for human habitation. Jackie stepped in, and (reportedly) spent more than $30,00 to restore the house to a liveable condition. But if we need the 'full' story to feel true empathy, what does that say about us as viewers? Are we judging based solely on the characters merits (or lack of), or does something else influence? Maybe it's an inherent fear of aging or death; of what happens once you begin to exist outside the 'norm'. Topics of discussion might centre on aristocracy, but they are a familiar rhetoric to most families – from mundane arguments about what to eat and who should feed the cat(s) to more 'serious' issues, such as marriage and men and finances. There's probably a little bit of the Edies in all of us, and maybe that's something we don't want to acknowledge.

Despite the squalor, and despite Little Edie's repeated and continued longings to escape, both seem remarkably happy with their chosen lot. There's no doubt that both women played up to the cameras. And perhaps their perception of normalcy was so off-kilter thanks to years of isolation they had no comprehension of how they would be perceived on-screen – Big Edie reportedly approved it prior to her death in 1977, and Little Edie penned a resounding endorsement following Walter Goodman's scathing attack on the documentary, published in the New York Times. In an era of scripted reality, there's a refreshing honesty to their actions – a lack of censorship and spontaneity that's all the more haunting and heart breaking because it's grounded in real-ness. If they weren't embarrassed by their portrayal, why should we be?

Personally, the embarrassment doesn't stem from their actions, rather the gradual understanding that it's likely that one – or both – of these women were suffering from some kind of mental illness (perhaps schizophrenia). Is it acceptable that this was packaged as 'entertainment'? Of course not, but it's impossible to imagine either Edie admitting to a (mental) fault and accepting anything that approached help. Happy to live in a shared world they had constructed, one built of memories and (partial) madness, it's impossible to conjecture if they would have been better in 'reality'. The documentary clearly captured heightened versions of each Edie's persona, but even without the camera they had already accepted who they were and what 'life' meant. And maybe there's something we can all learn from that.

Personally, the embarrassment doesn't stem from their actions, rather the gradual understanding that it's likely that one – or both – of these women were suffering from some kind of mental illness (perhaps schizophrenia). Is it acceptable that this was packaged as 'entertainment'? Of course not, but it's impossible to imagine either Edie admitting to a (mental) fault and accepting anything that approached help. Happy to live in a shared world they had constructed, one built of memories and (partial) madness, it's impossible to conjecture if they would have been better in 'reality'. The documentary clearly captured heightened versions of each Edie's persona, but even without the camera they had already accepted who they were and what 'life' meant. And maybe there's something we can all learn from that.

Further reading: The captivating monotony of Grey Gardens / 'Grey Gardens': cinema verite or sideshow? / Grey Gardens' Mad Women / My life at Grey Gardens: 13 months and beyond by Lois Wright

What Is The Disability Being Portrayed In Grey Gardens?

Source: https://girlsdofilm.wordpress.com/2015/01/04/grey-gardens-captivating-eccentricity-or-voyeuristic-exploitation/

Posted by: sherrellsiondonsen.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Is The Disability Being Portrayed In Grey Gardens?"

Post a Comment